Taxonomies for Unknowing

Coasts and Oceans

[+ Cosmologies of Care for Ghosts and Monsters]

Taxonomies of Unknowing was shown at the exhibition Neglected Topographies and Cosmologies of Care, by Wong Zihao, with Liu Diancong, 11-19 May 2024

The exhibition explored artmaking as an alternative practice of care for coasts and oceans,

and was an outcome of a call for proposals by Art Outreach, at their [Hearth] community space enabling emerging arts practices.

Look out for our upcoming plans where newer iterations of this art-mapping practice are in the pipeline, contributing to a larger project Mapping Intertidal Worlds.

Dragons, and other sea monsters, were depicted in very old maps as metaphorical representations to show where the boundary of known worlds met with the unknown—as is seen in Ptolemy’s Geographia (150 A.D.), his “Guide to Drawing the Earth”. They made visible on the map what could not be seen, and was yet to be known, and so acted as visual warnings to navigation: that beyond a certain boundary, one would be entering into uncharted waters. In the present century, whole landscapes previously thought uncharted, have become fully visualisable—charted, surveyed, measured, mapped—and through being seen in completion by the eye of the satellite, became known. The monsters eventually faded from the map’s watery borders.

Taxonomies for Unknowing Coasts and Oceans begins a process of unmapping and remapping (that is, reordering, recategorising, and refiguring—or more accurately put, scrambling) the relations between land and sea, and surface and depth, troubling as well the neat distinctions between human and more-than-human inhabitations (including those of sea spirits and monsters), and blurring further the mythic, fictive, and the real. The curious maps produced in the experimental un/re-mapping processes tell of alternative taxonomies of fluid and shape-shifting oceanic cosmologies where ghost islands traverse between visible and unseen worlds, and where sea monsters wander between the known and unknown, and mythic and real places.

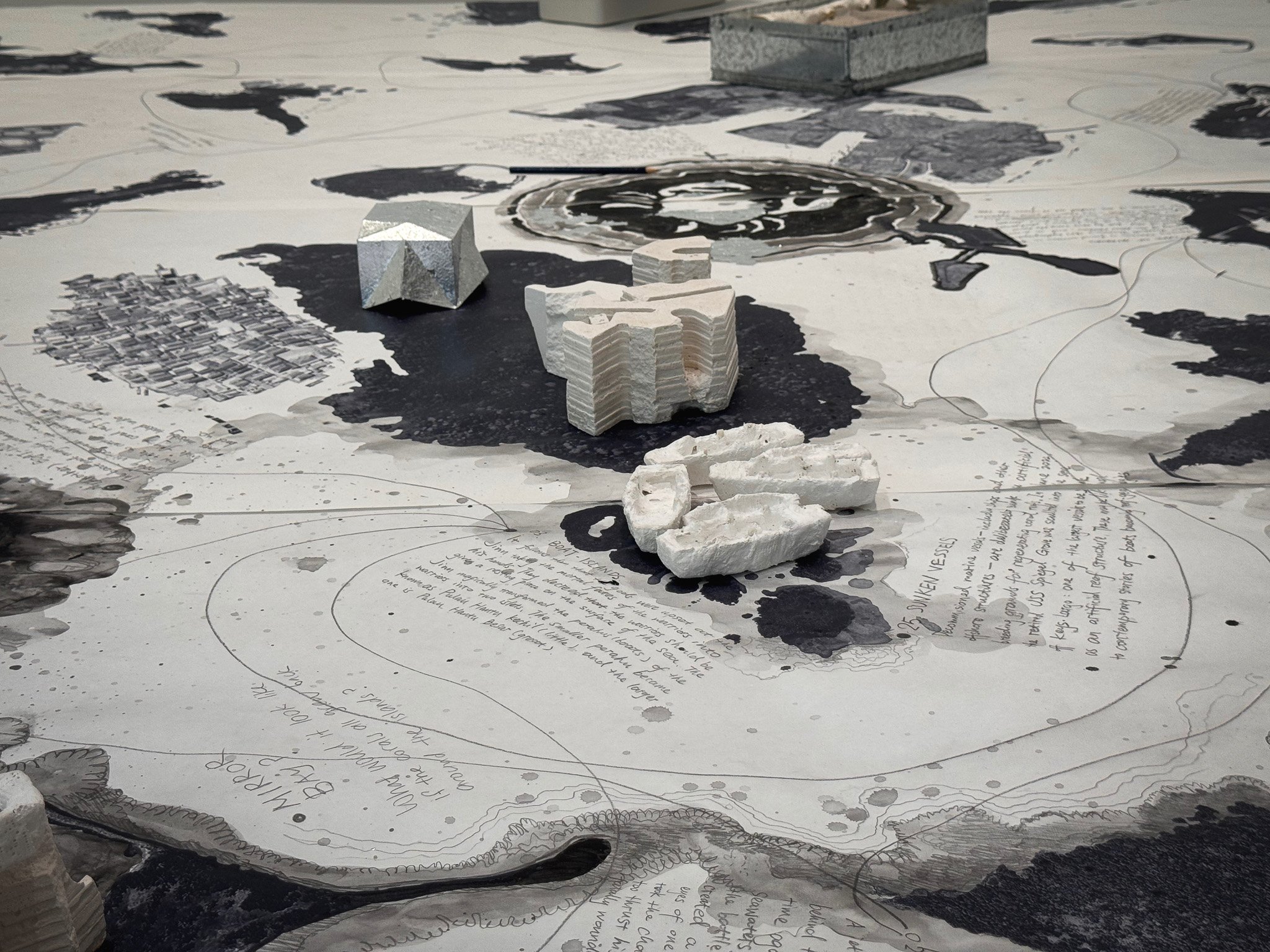

Cosmologies of Care [for Ghost Islands and Archipelagic Monsters] is a map that flows in multiple ways, to guide its readers along unexpected traverses and indeterminate routes, so that they might discover the unfamiliar once again within multiple and overlapping oceanic cosmologies, destabilising the realms of visible and invisible worlds, known and unknown, and real and unreal. Archipelagic geographies of islands, coastlines and waterways, trajectories of maritime vessels and historic landing points, and environmental phenomena and intertidal ecologies, collide and co-mingle with archaic and archival, as well as speculative and make-believe worlds, where cartographic ghosts and monsters roam unseen.

Indeed, Cosmologies of Care is a strange artefact to behold—a floor-sized map that could be trodden on, and keeps being redrawn. Such a map surely (mis)leads their readers to embark onto trajectories of unknowing, getting lost rather than finding any clarity on the subject. Yet this map that can traverse between worlds may speak new meaning into the dwindling remains of almost-vanishing—and hence neglected—cosmologies reminiscent of a forgotten time when the seas abounded with the nonmodern and supernatural figures of archipelagic ghosts and monsters.

Cosmologies of Care is a reminder to the island-city, and many other coastal cities elsewhere, that beyond technological solutions to the still-evolving environment and its changing climates and natures, lie the possibility of a future sea that may be returning to us in an ever-wilder state, evoking once again the sea monsters that metaphorically gave warning to the “unknown” worlds—and cosmologies—that awaited discovery.